Towards the end of Menewood there is a scene featuring a Nativity play. I’ve had at least two readers question whether it could have happened—by which I mean readers scoffing that it could not possibly have happened. To which I was very tempted to respond: Prove it. (Which, as an historical novelist, is the only bar I need to meet: that something, no matter how unlikely, was at least possible.) But I’m heavily invested in the events of Hild and Menewood not only being Not Impossible but being at the very least plausible, and preferably probable. So, given the season, I have assembled my evidence—warning: it is scanty! it is circumstantial!—as a post.

So: Would there have been nativity scenes in seventh-century Britain? Absolutely! Maybe. That is, it’s very definitely possible. And given human nature, I’d be more surprised if there were not than if there were.

Where do nativity scenes come from?

Supposedly St Francis of Assisi is to blame for all those interminable nativity plays school children and their cruel teachers use to both amuse and horrify their parents. In 1223, in Greccio, he celebrated midnight Mass in front of a life-sized nativity scene featuring live animals.

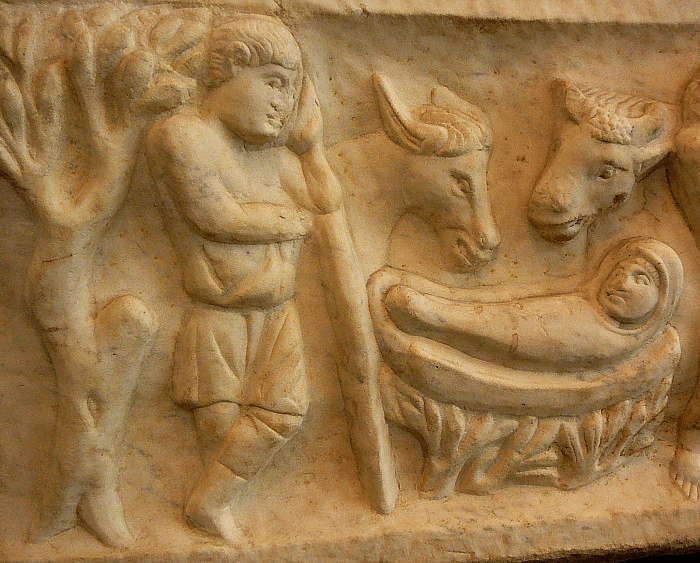

But, really, I’m guessing this stuff happened long before that. There’s very early evidence for nativity iconography. See, for example, the so-called ‘Sarcophagus of Stilicho’ dated by some to the late third or early fourth century:

There is also, apparently, a fourth-century sarcophagus lid from the Roman catacombs (now in the Pio Cristiano collection of the Vatican Museums) carved with a series of now-iconic nativity moments: the magi bringing gifts, baby Jesus in his manger—this one a sort of hay basket complete with ox and ass and a shepherd. I can’t find a legally-usable image of that, though you can see it here. But I did find this one:

But scenes aren’t plays

It seems pretty obvious that nativity scenes were around for centuries before Hild’s time. We also know that people were interested in the birth and and early life of Jesus, as evidenced by the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, which is one of the many so-called infancy gospels—attempts to backfill Jesus’s biography from birth to adolescence. (The composition date of Pseudo-Matthew is disputed, with some putting it between 600-625 CE,1 others stating it can’t possibly originate before 650,2 and yet others going for the ninth century.)

People are people: our basic nature doesn’t change. And people have always loved to listen to stories Even better, they like to watch stories. We human beings love performance! We know Ancient Greeks had a very well-developed theatre culture, e.g the Greek Tragedies of Euripides, Sophocles, and Aeschylus; Sappho wrote lyric poetry which is obviously performed to some degree; there was Roman theatre, Chinese theatre—so of course there would have been some kind of early medieval theatre.

We also know the early Church liked drama: the Quem quaeritis (an antecedent of the Passion Play) was officially part of Church liturgy from at least the tenth century.

If you add all the circumstantial evidence, it seems mildly ridiculous to suggest there could not have been nativity plays in seventh-century Britain.

So why put one in?

Why not? Nativity plays—at least the modern myths surrounding them—are funny. Also, I just wanted to; it gave me vast delight and made me grin.

Here’s a snippet from near the end of the book during a peaceful midwinter interlude before really gearing up for the final battle. Things you need to know: James is James the Deacon; Maer is a six-year old orphan; Fllur is a badly abused young woman who is beginning to recover, and Geren is her infant son; Clut is a cat; Brona is a butcher. Hild has paid for a new church which is built but still being prettified with decoration. James the Deacon meets her there one afternoon…

Hild stared at the beast surrounded by children. "Why is there an ass in the church?"

"Because Joseph put Mary on it to escape," Maer piped up.

For the first time in Hild's memory Fllur was beaming. "And my Geren is baby Jesus!"

"He is?" Hild saw a rough wooden crate. She frowned. "Is that hay? What's it doing here?"

"It's a manger," Maer said.

Hild turned to James. "You said to come listen to singing."

"And there will be singing! Just as soon as the three wise men have found their drums."

"Their...?" Three children, one of whom she did not know, seemed to be squabbling over something in the corner. Just then Clut sauntered in, tail up, and Hild decided there were many other things that needed her attention.

#

That night she told Brona about the hunting lessons. "Are you sure you don't want to learn?"

"I kill enough things. I just like the way you tell the stories."

And Hild realised how much she wanted to show Brona more things, to watch that moment when understanding lit like a candle behind her eyes. Like teaching Maer about broom and birch twigs, or Wilfrid how to count--though that was not going well. "Well, I won't be taking anyone hunting until after Christ Mass. Tomorrow night before the feast James is very eager for me to admire his story and music."

Brona laughed: Hild had told her about the ass in the church and the three wise men fighting.

She grinned. "Don't laugh too soon. They have persuaded me to let them perform in the longhouse before the feast--so you'll be watching, too. We all will."

#

When all the blood and dung had been cleaned up, the ass led away in disgrace, and the children consoled with honeycomb, the appreciative crowd wiped their eyes and found places on the crowded benches. Luftmær struck up a merry tune, and while Aldred, Almund, and Aldnoth sang--their voices fit beautifully together--the food began to arrive.

James joined them on the bench. "Well, that could have gone better."

"No, no," Oeric said, grinning. "It was just what we needed."

"Better than a mummers show!" Grimhun agreed.

"I howled when Joseph whacked the wise man for saying Jesus had piddled in the manger," Begu said.

"And when the ass started eating the hay and tumbled poor old Geren, I mean Jesus, out of the manger--"

"And Mary tried to pull it away--"

"And then the ass dropped dung all down her dress!"

And they were all laughing helplessly again.

"With hindsight," James said, "my mistake was not feeding the children earlier--"

"Or making them all use the pot first," Gwladus said, and speared a sausage before passing the platter on.

"That too. The song they were to sing really could have been lovely."

"Were they supposed to bang their drums and shout at the beginning? When the angel--"

"I liked the angel's halo," Begu said.

"One of Rulf's hoops painted yellow," Hild said. She passed on the sausage; she would wait for the thick roll of doe haunch just coming off the spit.

"No," James said. "The banging and shouting and jubilation was supposed to be during the second song, the song of triumph--when the angel declares that the baby will be Christ the Saviour. The children got excited."

"Maer does get a bit previous when she's excited," Sintiadd said as she filled cups.

"Which part was that?"

"Right after they named the child," Hild said.

Brona laughed, and imitated boy-Joseph's high-pitched voice. "What shall we call him?"

"I know!" said Gladmær in a surprisingly good imitation of Maer's sturdy Elmet accent. "We'll call him Berht!"

"Or Du!"

"Or Ulf!

"Wait, I know!" Brona gave them a significant look and they all joined in: "Let's call him Jesus!" Then they all howled again.

"You should do that every year," Hild said to James. "Imagine how splendid it could be when we have a proper hall." And when they would not have to risk their precious horse blankets, worn by the wise men, being trampled in a fight.

"I fear no bishop would approve of such levity," he said.

And Hild realised that if her plan worked, there would once again be bishops in the north. The question was, whose bishops?

Those readers of a certain age who, like me, grew up in Yorkshire may hear echoes in this scene of a certain primary school nativity play staged in Sheffield (I think—pretty sure it was south Yorkshire) in the 70s or maybe early 80s and televised by BBC North. Or maybe it was Calendar (ITV). Either way, I remember that particular episode fondly, even today…

Excellent points and a great story sample! I love how the lightheartedness gives way to the questions; the question of whether this is where a tradition began, and Hild’s question about the bishops. Great blog!

700’s? Mummers as well? You ARE stretching things. OTOH leave us not let the truth stand in the way of a good story.

600s actually 🙂 And ‘mummers’ not so much in the 14th-century sense but as travelling players (who I’d argue have existed since people have) and, anyway, could very possibly have been where mummers began. But, yes, absolutely, to me when it comes to amusing interludes in fiction, the rules are allowed to be a bit looser…

I agree with you — who’s to know? So very very much of how they lived is undocumented. But they did tell stories, make music, and sing. We can’t know that in some part of the country at some time, there wasn’t a telling of the birth of Jesus with props.