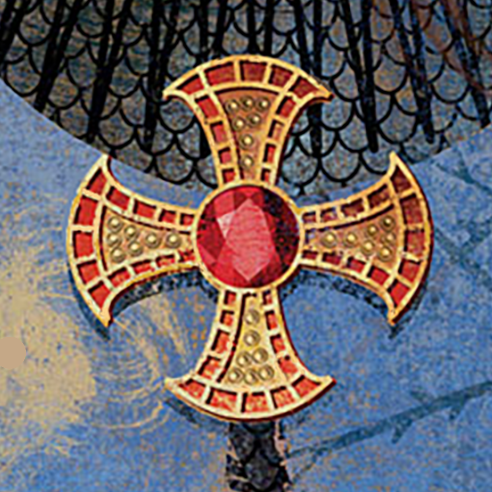

The cross Hild wears in Hild and Menewood is nothing like the one illustrated so beautifully on the covers by the fabulous Balbusso twins. (Though at some point in her journey it will be.)

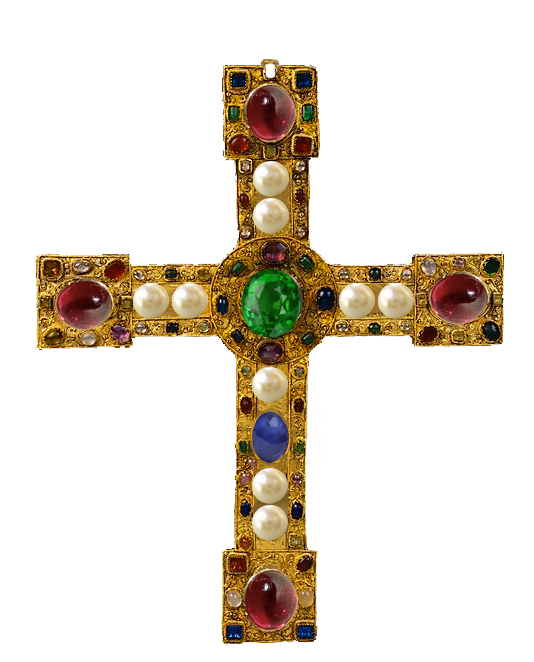

The cross Edwin gives Hild in the first book, and that she wears through the ending of the sequel, is a much more ornate and traditionally Western European object: a hefty, traditional cross shape in solid gold with the long upright and shorter cross piece inset with a row of big pearls, and perhaps a large emerald or garnet at the centre, and probably an assortment of other coloured gems here and there. Not a simple or minimalist piece but gaudy, big, bright and bold—just not in Hild’s favourite colours. I imagine it as a diplomatic gift to Edwin either from some polity seeking trade and influence or one reinforcing its notions of hegemony.

Something like this—designed to be hung around the neck—only even gaudier. This is one I made from bits and pieces of images of real crosses, though it has much more colour symmetry than some of the jewels of the time. Note the nine pearls, which Hild found very useful during Menewood. (She sacrificed them without a pang—she never really liked this cross.)

The big problem, apart from the fact that it just wasn’t really to Hild’s taste, is that it would be seriously impractical to have something that heavy hanging from your neck and swinging out freely, particularly for someone as physical as Hild.

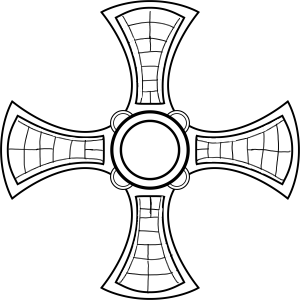

The cross on the covers is a direct copy of the seventh-century Trumpington Cross, though with a faceted stone in the centre rather than what is either a foiled slice of garnet or red enamel in the original. And it’s very like the one I imagine Hild commissions and wears from Book 3 on—for formal occasions. It would be a subtle piece, a version of the cross pattée, with its origins in the deep past and so hinting at more than one cultural belief system—think sun cross, and even Thor’s hammer. This one, with its rounded ends, is (according to Wikipeida) a croix pattée alésée arrondie. Simultaneously gorgeous, rich, and deceptively simple. The closest comparison might be with Cuthbert’s pectoral cross: an equal-armed gold body inset with garnet; simple and radially symmetrical, like a propellor or a fan blade.

Cuthbert’s cross is made of small garnets—little bigger than garnet chips—in typical cloisonné style. The larger central garnet is backed by piece of white Mediterranean shell to brighten its colour. Four cabochon garnets sit between the arms of the cross. It was worn on a silk and gold string. Maybe beaded gold around the edges and rims for extra glitter (hard to tell from the lo-res pics I could find) About 6cm wide.

This kind of perfect symmetry would be deeply appealing to Hild. But she would have used bigger garnets and they would have been foiled for extra glimmer and sparkle—she was richer than Cuthbert, and royal. Given that her favourite colour (at least as I’ve conceived her) is blue there would have been either blue enamel or perhaps lapis lazuli. And she wanted it to be seen—so perhaps some contrasting white, whether enamel or mother-of-pearl or shell (or, if she were feeling very rich, actual pearls). She may also have preferred something simpler. After all, she lived, worked, and fought in very physical situations: the fewer fiddly bits to snag on anything, the better.

But even something that simple would would be impractical for battle. I taught women’s self-defence for many years—and what I learnt is part of the reason that I have very short hair, don’t use earrings, and never, ever wear anything grabbable around my neck. (I have one necklace; it’s closely-fitting—it won’t snag by accident and if someone with ill intent gets close enough to grab it, I have more to worry about.)

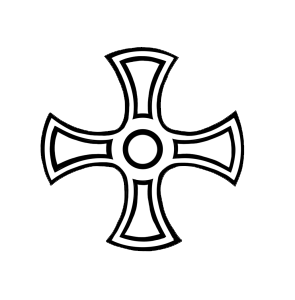

So in more dangerous situations, I decided Hild would wear a cross in the form of a thick medallion, a bit like a roundel, and it would be sewn/tied onto her outer wear, and visible—very visible—in the heat of battle.

Here’s what I came up with:

Strictly speaking that central garnet should be cabochon-cut—both because that’s what the Early Medieval goldsmiths used, and because it’s more resistant to damage in a fight. But the faceted kind looks more sparkly—and also more of a nod towards the original art of Hild and Menewood—so, eh, I used that. It’s designed to be seen, to be seamless, and to be sewn/tied on—whether with silk or gold thread to cloth, or with leather to leather or ring armour—though of course it could be worn around the neck, too. Given its shape and design, this could afford to be bigger than Cuthbert’s cross—perhaps as much as 8 cm, and worn right over the centre of the chest. (With the body of the disc being bronze, it would in itself provide a little extra protection from, say, an arrow.) After all, Hild is a big woman, and when it comes to Early Medieval bling, size really does matter.

Also I just had enormous fun working out how to make it. I love making pretties—and, unlike gold-smithing, when you do it digitally it costs nothing but time…

Thank you for writing (and illustrating) this Nicola! I’m always interested in the look of Hild and her world and this was absolutely fascinating.

My pleasure! I love sharing my world.

Being a Pacifist with God does not mean I have not considered how I would be armored when I went ‘into the field of conflict.’ Wearing a cross with a cord around your neck presents a lot of problems when you are moving around and it would not help you with offense and would imped defense. The Chaplains during Vietmam wore flax jackets and steel helmets during times of potential risk. In the early part of the war they wore a small gold cross on their lapels, but when it was realised that this increased a sniper’s focus on them as targets, they then wore the crosses on the inside of the lapels. Weight of your armor is a serious concern. A smaller man like myself, would have trouble wearing the armor the military and law enforcement wear today.