** SPOILER WARNING: If you’re not familiar with early 7th-century insular politics and it might bother you to know in advance of reading Menewood which kings killed which and when, stop reading here **

In the Hild sequel Menewood (1) there are two main antagonists, Penda and Cadwallon. Penda remains mostly offstage (his star turn comes in a future novel), which leaves Cadwallon front and centre. For Hild, published nearly eight years ago, I assumed, as most people do, that Cadwallon—whom Bede in HE calls Caedualla res Brettonum—was Cadwallon ap Cadfan, king of Gwynedd. In that first novel he perennially clashes with Edwin and is roundly beaten every time, except in one engagement in which he allies with Penda, a Mercian war-leader. I began Menewood with the same assumption—but just as I neared the end of the first draft I came across Alex Woolf’s suggestion that the story of the era would make more sense if Cadwallon had been a northern Briton.(2) Much of what he has to say is very attractive, particularly when it comes to the family trees of the north.

At this stage I can’t revise my initial notions of Cadwallon—it’s already out there in a hundred thousand copies of Hild—but as I await editorial comment on Menewood I find myself wondering: If I hadn’t already published Hild, which argument would I lean towards, Cadwallon, war leader of Gwynedd and neighbour of Mercia, or Cadwallon, son of the North, war leader and/or petty king of some people between the Roman walls?

After totting up the arguments on both sides, there was one point that in my opinion outweighed all the others—geography (3)—and I was pleased to find that, on balance, I was probably right to regard Cadwallon as a man of Gwynedd.

Cadwallon being from Gwynedd helps to make sense of some events from the early part of Edwin’s kingship, such as Edwin besieging Cadwallon on Glannauc, a tiny island off Anglesey—though of course Woolf has some thoughts about that (4). For me, the main point to bear in mind is that if Cadwallon were from north of the wall, the Battle of Hæðfeld/Hatfield Chase, would make absolutely no sense. (A brief summary of the battle: according to Bede, Cadwallon, in alliance with Penda of Mercia—not yet king, but probably a war-leading ætheling—slaughters Edwin, king of Northumbria and Anglisc overking, together with his son Osfrith Yffing—Eadfrith Yffing, the other Northumbrian ætheling, is killed later by Penda—and the majority of the massive Northumbrian warband. After Edwin and Osfrith are beheaded, Cadwallon and Penda then head north through Elmet and Deira, enacting, according to Bede, a terrible slaughter.)

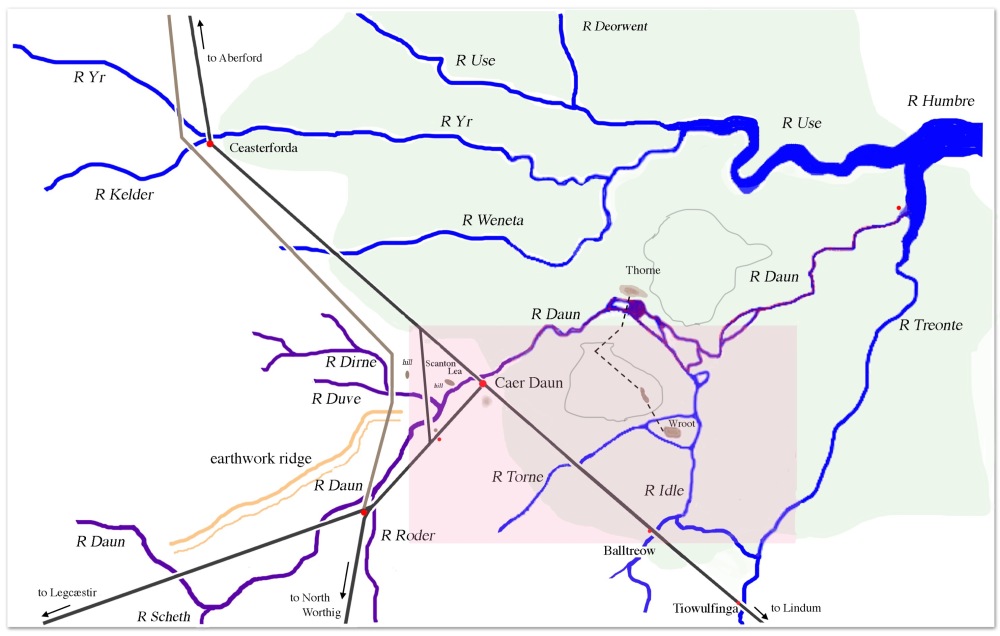

The Battle of Hæðfeld is assumed to have occurred at Hatfield Chase, the moor lying between, on the west, the easterly branch of Ermine Street, the Roman road that runs from Lincoln to York, and, in the east, the wetlands of the Elmet/Lindsey border. Before Vermuyden’s massive drainage project in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, which reset many watercourses, these wetlands were extensive swamp, alluvial plain, and a brackish sea; in autumn and winter they could probably be traversed only in a boat or via the Roman road (a branch of Ermine Street). This road was the superhighway from London to Lincoln to York, the heart of Deira, and from York it becomes Dere Street, running north to Hadrian’s Wall and then more northerly still, through the heartlands of Bernicia, to the Antonine Wall. This road was used so many times by warbands and armies approaching Northumbria from the south that it could be referred to as the war-street. (5)

Hatfield lies at the extreme southern boundary of old Elmet, itself the southernmost region of Deira—which in turn is the southernmost kingdom of Northumbria. If Cadwallon was a northern Briton, based beyond Hadrian’s Wall, presumably his warband was too. So why would Edwin, king of Northumbria, permit a warband (and conventions of the day—specifically, the Laws of Ine—described a group of 35 or more armed men a warband) to travel unmolested from beyond Hadrian’s wall south down Dere Street, through the richest parts of Bernicia, to York and the richest parts of Deira, and then further south still, all the way to the very southern edge of same before trying to stop him? He would not. He would meet the enemy warband at the first challenge/opportunity: when they first approach the border of his territory. To me, therefore, Edwin was facing an army coming from the south, from Mercia and/or Gwynedd.

Here’s the area shaded on the above map, which uses a mix of Old English and Brythonic names because those are the names Hild would have heard in her time there. The wetland is in green, and the original course of the River Don/Daun (pre-Vermuyden) is highlighted in purple.

And here’s the even more detailed shaded area on that map. The only areas reliably above sea level in autumn and winter would be Ynys Coed/Lindholme, Ynys Bwyell/Axholme, Wroot, and Crowle, with parts of Hædðfeld Moor and Thorne Moor traversable via defined pathways. The little maroon dot is where Hild spends time after the battle: in High Brune on Axholme/Ynys Bwyell. Right where that little yellow dot is, on Lindholme/Ynys Coed, is where I think it’s likely Edwin lost his head:

Anyway, after lots of happy battle slaughtering of Northumbrians, for a while we hear no more from Bede about Penda, except that he becomes king of Mercia. Meanwhile, Cadwallon spends over a year wandering around Northumbria ravaging, burning, and slaughtering anything that even smells of Yffings or Idings. If Cadwallon was from Gwynedd, and Northumbria was enemy territory, this is difficult to understand. How was he feeding himself and maintaining a big warband? There again, it’s even more difficult to understand if he’s a northern Briton. Slaughter, ravagement, and burning are not the behaviours of a man trying to become overking of the north. Overkingship requires alliances, it requires being seen to be a Good Thing for the Economy, and other stability-influencing and/or riches-inducing factors. Yet Bede and various British annalists make no mention anywhere of Cadwallon building: building agriculture, roads, wics, herds, churches, other religious foundations, marriage alliances, an army, palaces, vills, peace, or, well, anything. Either he was from Gwynedd and not intending to stay, or he already had a kingdom in the north and didn’t need to build it.

But if Cadwallon was a son of the north—I can imagine him as a chief, say, of one of the minor peoples subsumed by the Gododdin, a coalition now separating into their components parts: no longer Gododdin but once again the peoples of Bryneich, Arfderydd, Calchfynydd etc.—he would need to be building alliances with bigger kingdoms such as Rheged and Alt Clut. He would most definitely not be pissing off powerful groups like the Picts (who fostered Eanfrid Iding and might not be thrilled to find their investment ruined (6)) and Dál Riatans (who fostered Oswald, Oswiu, and Æbbe Iding; ditto) who could sweep down and eat him for breakfast. Yet we hear nothing of this. There again, if Cadwallon was no longer king in Gwynedd—deposed after Edwin besieged him on Glannauc—and had become, instead, a mercenary warlord, then perhaps he was simply asset-stripping, gathering all the gold he could before running back south and west with the loot to finance his retaking of the Gwynedd throne…

…with or without an alliance with Penda. That alliance is itself another point in favour of Cadwallon being from Gwynedd. For convenience, in these novels I call Penda king of Mercia from the beginning but I suspect that at this point he was more the war leader who eventually becomes king. But for the sake of argument let’s say he was king, with the power to form diplomatic relations with another ruler. How would he go about doing that if he was based in Mercia, and Cadwallon in, say, far northeast Britain? It’s hard to exchange diplomatic notes when your two countries are separated by two or three hundred miles of enemy territory—and, oh, one of the parties might not be literate. (I say ‘might’ advisedly—but that’s not a discussion for this post.) There aren’t particularly easy sea routes between the two groups, either. But communication between Mercia and Gwynedd on the other hand? Go look at the that first map: easy! They’re practically next door! It makes total sense that Cadwallon and Penda would forge a neighbours alliance.

In the end, geography for me is what makes sense of the Cadwallon/Penda alliance, the Battle of Hæðfeld, and Cadwallon’s harrowing (if you trust Bede) of the north. But isi still difficult to make make sense, whichever way you slice it, it’s Hild’s Oswald’s defeat of Cadwallon at Deniseburna, also known as the Battle of Heavenfield. (I linked to this very short article because everything else you’ll read in places like Wikipedia are rubbish: full of imagined events stated as fact.) Think about it. Cadwallon has spent a year in the north. He’s (probably) using Corbridge/Corabrig, which is (probably) still in good repair and (definitely) a marvellously strategic redoubt athwart Dere Street and the River Tine, as his base. He has a ton of gold, he has an undefeated warband—which by this point would have been massive (because he had a lot of gold to share with his followers)—and after all this time he would know the terrain well.

So how come Oswald, greatly outnumbered according to Bede—and of course he would have to be, because he’s coming from Dál Riata, and so (probably) by sea—and in unknown territory, manages to defeat him? Why wouldn’t Cadwallon just sit tight with his hoard of gold and provisions eating bonbons while Oswald dashes himself uselessly against the walls? Bede explains it through visions and divine intervention but, well, I prefer something more tangible. That is, Hild.

Specifically, Hild’s ability to read the weather, build alliances, persuade others to follow her on no more evidence than he word, and her understanding of hydrology and the specific gravity of gold. To whet your appetite further, here’s a super accurate GIS-based map of the battleground which one day I’ll happily explain in detail but not until at least a smattering of people have had the chance to read the novel. (Which will be a while because publishing operates on geological rather than human time, it’s a long novel, and the battle comes near the end.)Today I’ll say only that this map was made possible through the most excellent skills of the wonderful Tenaya Jorgensen to whom I’m greatly indebted:

And here, for grins, is my topographical map of same, still very rough. Before publication I’ll polish it up nicely for my new website. But I’m trying to use different sets of maps in this post to see which style works best. If you have opinions about that, please leave a comment below.

Speaking of fortified towns, and Cadwallon, Osric’s defeat and death in Deira a year before Deniseburna again doesn’t make much sense. According to Bede Osric claimed the kingship of Deira and besieged Cadwallon in a fortified town. Cadwallon made an unexpected sortie and slaughtered Osric and his men, then happily resumed his harrowing of the north. Again, this was most likely on Dere Street (where most fortified towns in Deira were to be found). I’ve assumed Aldborough, which I’ve called Urburgh—fortified town on the River Ur/e.

I spent a long time thinking about this, about how an invading warband—now half its original size (7)—in enemy territory could defeat a king’s army on home turf. And, again, it comes down to geography and frankly Osric’s stupidity (which thankfully I had already established in Hild, so it’s not merely Idiot Plot syndrome (8)). Again, you’ll have to wait for the novel to find out how, exactly, it all unfolds.

In order to make sense of Cadwallon and his series of honestly eyebrow-raising victories and defeats, I have had to assume that although he is very cunning and quite strategic—not an idiot—he is also motivated by hatred of all things Iding and Yffing (something, again, I set up in Hild), and a greed that on occasion overwhelms sense. At Deniseburna he loses to a numerically inferior force because the other side’s strategy is architected by a genius of observation (Hild) and because Cadwallon just can’t help trying to squeeze in one last grab-the-loot-and-run raid before he runs for home—which is, I believe, Gwynedd.

(1) Menewood is finished, rewritten once, and now awaiting editorial comment. Publication is probably about two years away.

(2) A. Woolf, Caedualla res Brettonum, Northern History XLI: 1, March 2004. In which Wolfe seems to base much of is argument on the prose styles of scribes. It’s pretty interesting stuff—the kind of thing I’d love to talk about over a pint—but I can’t *quite* buy it.

(3) More particularly geography and geology: the influence of the natural landscape on people, society, and events.

(4) Which I won’t reprise here as it’s not the main point of my argument.

(5) Other battles that occurred on or near Ermine Street/Dere Street in the seventh century probably include (probably) the Battle of the Winwæd and the Battle of the River Idle. I have no doubt there are others.

(6) According to Bede, Eanfrid Iding and twelve chosen companions went to Cadwallon to parley, and were murdered out of hand.

(7) At this point Penda has taken his spoils, left it all to Cadwallon and gone home in disgust.

(8) Idiot Plot Syndrome is the necessity for a character to be an idiot for the plot to make sense. You know: all those people in thrillers being chased by unknown assailants who split up to be picked off one by one instead of sticking together, or who don’t answer the phone or read the text from the person with vital information, or the character in the horror novel blithely traipsing down the basement steps into the dark…

I love this vivid, coherently discursive, self-arguing history. I’d have all my history written so.

@Jim: I have to say, me too!

Yes, Cadwallon of Gwynedd, but he could have had maternal ties to the north. So what do you do with Eowa, Penda’s brother?

@Michelle I used writer’s privilege and completely ignored him 🙂 I’m only going to really talk about Mercia and Mercian politics when we get to the marrying-Penda’s-relatives stage. MENEWOOD is already super long; putting all that stuff in would have made it *too* long…

Fascinating stuff as usual! Can’t wait for the book. But I think that should be Alex Woolf.

@Pete Aaargh! You’re absolutely right: Woolf. I’ve fixed it.

Could you share your reason for calling York “York” when nobody in the 7th century was calling it that? Why not Eoforwic?

@Karen When I first started writing, I decided that ‘Eoforwic’ might be a step too far for the general reader whereas ‘York’ would give them a sense of easily-recognisable geography, an anchor they could cling to. As I wrote and rewrote I began to change my mind—but was never quite decided enough to change it. And now I’m stuck with it.

I admit that right now I’m wondering if I can change it—and fix one or two other errors along the way for a new edition to coincide with the release of Menewood. If I can, I will. We’ll see.

Fantastic, can’t wait for Menewood. I also got a lot out of Max Adams’s The King In The North.

Having just finished (and absolutely loved!) Menewood, I can attest that the reasonings and strategic thinking you develop for Hild and Cadwallon come through absolutely brilliantly in the narrative! I was so bought-in for all of the chapters in which Hild is maneuvering her bands leading up to the final battle at Heavenfield – just totally gripped and feeling right in on the action.

All to say, I think you did a masterful job integrating the operational strategy and on-the-ground tactical approach and the overall story narrative, all wrapped in your beautifully vivid prose, and Menewood had everything I look for in books and so rarely find.

When planning out campaign/battle portions of your books, are there specific authors or books that helped give you inspiration or that you found to be helpful examples (whether of things done well or not-so-well)?

There was no single book, no. Rather it was a lifetime of reading omnivorously—popular history articles, past andpresent; blogs by armchair enthusiasts; old collections of data(and speculation) about Roman roads; farmer’s almanacs about crop yields; old law codes about what constitutes an ‘army’; discussion on various forums about horse breeds, load-bearing capacity, feed requirements; old maritime lading bills (how much meat/grain/water would you need per mouth for a 6-month voyage)… Well, the list is almost endless! I’d say the most important thing I did was ignore all fiction ever written about ancient, antique, and Early Medieval warfare—because it’s either written purely for effect, or based on a mix of wish-fulfillment, superficial research (just because a horse of x breed these days can travel n miles a day for y number of days while requiring z pounds of fodder doesn’t mean that was true for other times and places), and gleeful invention. I get so tired of reading otherwise-delightful novels and throwing it down muttering, But how did you feed and water the horses inthis barren wasteland?!